Summary :

“No forgetting” is the name of a series of articles and publications related to stories of people who died as a result of the consequences of the Swiss state, its laws, its police, its prisons. Because remembering is necessary for the struggles of today and tomorrow.

This issue is a collaboration between Projet-Evasions and @joujou_tdj

The story of Oleg N.

For a summary of the life of Oleg N. we have republished the article from the newspaper WOZ here, written by Bettina Dyttrich, which gives a good overview of the events of the time.

In this article, it is mentioned that Oleg liked to read and discuss the texts of the anarchist Bakunin. “Do you want to make it impossible for anyone to oppress his fellow-man ? Then make sure that no one shall possess power” he said. The insubordination proper to the queer and anarchist spirit showed in Oleg’s refusal to let others decide about his life, his sexuality, the place where he wishes to live. As for so many people, power and authority where the obstacles that keept Oleg from a freely chosen life.

Facing Oleg are multiple state structures and systems of oppression. Patriarchy, which seeks to impose him to be straight and homophobia, which seeks to restrict his sexuality. The psycho-normality which sees in any non-majority human expression an act of madness and in any psychological vulnerability a mental disorder. And then the authoritarian state structures, with their police, their borders, their migration laws that allow or deny the right of a living being to come and live where they wish.

Oleg’s story is, however, one of confinement by norms, as well as of escape. At birth, Oleg is assigned straight, by default, like all little boys in a hetero-patriarchal society. Yet Oleg will become homosexual. He is assigned male, which will not prevent him from dressing as a woman. He is assigned Russian but will still try to go to France, Luxembourg, Germany and Switzerland.

Even though Oleg was a victim of many different oppressions, his life is also full of resistance and it is this side that we want to keep in mind. We don’t want to see Oleg as a hero nor a martyr, but as a person who refused to let himself be locked up.

A life is a unique path, varied, abundant. So is Oleg’s life. But if each story is unique, many are similar and unfortunately Oleg’s case is not unique. People crushed by forms of authority such as social norms or laws are multiple. Keeping in mind the life and death of Oleg and its causes is also keeping in mind all the other people, known or not, victims of homophobia, police violence, imprisonment or deportation.

“Freedom is not an idea but a practice” said Bakounine. Let’s become accomplices of all those who in their lives fight for this practice and against all forms of authority.

Not only the body full of scars

Article published in the newspaper WOZ on the 22.11.2012 By Bettina Dyttrich

The search for adventure and a life without police harassment ended in the airport prison: The gay Russian refugee Oleg N. took his own life in the deportation prison in Kloten.

In the end, all he wanted was to get out. Out of prison, out of this country where the police always came right away. Maybe even back to Russia – although no one was waiting for him there.

Oleg N. came from Nizhny Novgorod, the fifth largest city in Russia. In Western Europe he was looking for freedom and love adventures. Instead, he found prisons and psychiatric hospitals. On the night of November 11-12, Oleg N. hanged himself in the Kloten deportation prison. He was 28 years old.

On November 16, over a hundred people marched through Zurich’s Bahnhofstrasse with candles in memory of Oleg N.. Martina Fritschy and Regula Ott are also there. They are activists with Queeramnesty, the subgroup of Amnesty International that campaigns for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights. Both had close contact with Oleg N.

“Oleg was queer,” Fritschy says in her eulogy. “Not just because he was gay. Oleg was queer because he embodied a strange and at the same time fascinating resistance. Never did Oleg bow with submissive devotion to the bureaucratic processes of the Swiss asylum system.“

Pushed out of the window

In 2004, Oleg N. travels to the West for the first time. He unsuccessfully applies for asylum in France, Belgium and Luxembourg. At the end of 2005, he returns to Russia.

On a September day in 2006, he goes for a walk in Nizhny Novgorod. He is wearing women’s clothes. The police arrest him, interrogate him, and let him go. Two days later, two policemen show up at his home. They insult him and push him out of the window. He falls several floors, breaks his pelvis, a shoulder and several ribs, loses a lot of blood, has ruptures in his liver and lungs. In the hospital, his spleen has to be removed. When he is able to return home after two months, he wants to press charges. An official advises him against it. Oleg N. does it anyway – and is taken to a psychiatric clinic by the police.

“His statements were credible,” says Denise Graf of Amnesty International. “And his body was full of scars. We know that there are serious abuses against LGBT people in Russia. We know of similar cases.“

Graf first meets Oleg N. in early 2008. Just released from the hospital, he has left the country and applied for asylum in the Principality of Liechtenstein. Soon he travels on to Germany and submits a second one. Both are rejected. In the fall of 2008, he is back in Russia, and again the police come. For more than three years, he is interned in a clinic in his hometown.

“Oleg didn’t understand the migration system,” Martina Fritschy says. “Not because he was too stupid – he was just psychologically often unable to behave as the authorities expected. In manic phases, he liked to travel around.” When his mental problems began and how much they had to do with his experiences in Russia, she does not know. But all the hospital stays couldn’t drive out his interest in the world. He loved to read, raved about Prosper Mérimée’s novella “Carmen” and discussed the theories of the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin.

On February 5, 2012, Oleg N. arrives in Kreuzlingen with a forged Estonian passport. In the initial interrogation, he describes in detail what happened in 2006. “What he told in Liechtenstein and in Switzerland was consistent,” says Denise Graf – not self-evident in a man with a severe psychological condition and a gap of four years. In a store in Kreuzlingen, he attracts attention because he knocks over a trash can. He comes to asylum shelters in Zollikon, then in Zurich. On April 21, he wants to go swimming in the ice-cold Lake of Lucerne – preventive detention (FFE). He stays three days in the Psychiatric University Hospital in Zurich. Then he jumps fully clothed from a Limmat boat and gets the second FFE, only a week after the first.

“Obviously, someone had to rescue him,” Martina Fritschy says. “But Oleg told me he just liked swimming. He found Switzerland a narrow-minded country: the police always come right away.“

This time, Oleg N. stays in the clinic for more than a month. On June 1, he takes off, traveling to Belgium – where he ends up in a psychiatric ward again – and to France. Shortly before, the Federal Office for Migration (FOM) invited him to a hearing. But the mail no longer reaches him. He had “grossly violated his duty to cooperate and thus expressed his disinterest in continuing the asylum procedure,” the FOM says. Oleg N. receives a decision not to enter the country.

Sexual orientation or gender identity are not explicitly considered grounds for asylum in Switzerland. A motion by former Green National Councilor Katharina Prelicz-Huber wanted to change that. But almost two-thirds of the National Council rejected it in 2010. Queeramnesty supported the request with a petition, but Martina Fritschy remains skeptical: “Homosexuality and transgender are Western concepts. Not all queer refugees can or want to call themselves that.” According to Fritschy, the legal framework would already be sufficient to grant them protection if the authorities were sensitive enough.

Melanie Aebli of the asylum counseling center Freiplatzaktion Zürich agrees: “Many refugees don’t know whether it’s offensive to talk about homosexuality in Switzerland. Or they are afraid because a person from their own country translates the conversation. These can be reasons why they don’t mention their sexual orientation in the initial interview.” Those who come up with it later are quickly seen as untrustworthy.

Banned from the psychiatric ward

In the fall of 2012, Oleg N. returns to Zurich. Soon he is back at the Psychiatric University Hospital and reports to Queeramnesty. Fritschy and Ott visit him on October 13. He deals with returning to Russia. He issues a power of attorney to Fritschy so that she can obtain documents for him at the FOM and wants to report to Return Assistance after his release from the psychiatric hospital.

But it never gets that far.

On Friday, October 19, Oleg N. is released, but goes back to the clinic on Sunday for a doctor’s appointment. What happens then is unclear. In any case, the staff reports him for sexual harassment and he is banned from the premises. That same evening, he is arrested by the railroad police. The police report states that he had harassed people in Zurich Stadelhofen.

In the preparatory detention, a doctor judges him to be “fit for imprisonment”. Oleg N. is taken to the deportation prison in Kloten on Sunday evening. According to interrogation protocols, he emphasizes that he wants to return to Russia. However, he also tells an employee of the Red Cross that he would like to apply for reconsideration. On November 9, Oleg N. is able to talk to his mother on the phone because the Red Cross lends him a phone. He asks her to get him papers so that he can leave the country. But the mother wants nothing more to do with her gay son.

Three days later, Oleg N. is dead.

The public prosecutor’s office Winterthur-Unterland has opened an investigation. According to the Zurich Office of Corrections, there had been no indications of a suicide threat.

Independent investigation demanded

Amnesty International is calling for an independent investigation into whether the suicide could have been prevented: “People who are so mentally distressed do not belong in deportation detention,” says Denise Graf.

Why was Oleg N. taken to prison on October 21 and not to a psychiatric ward? The doctor who classified him as fit for detention cannot be reached this week. And why did the authorities not support him in a voluntary departure? Because of the ongoing proceedings, the migration office cannot provide any information.

The next suicide followed just five days later: on Saturday, November 17, an Eritrean asylum seeker took her own life in the psychiatric clinic in Liestal. According to the “Basellandschaftliche Zeitung”, she was to be deported to Italy. She leaves behind three small children.

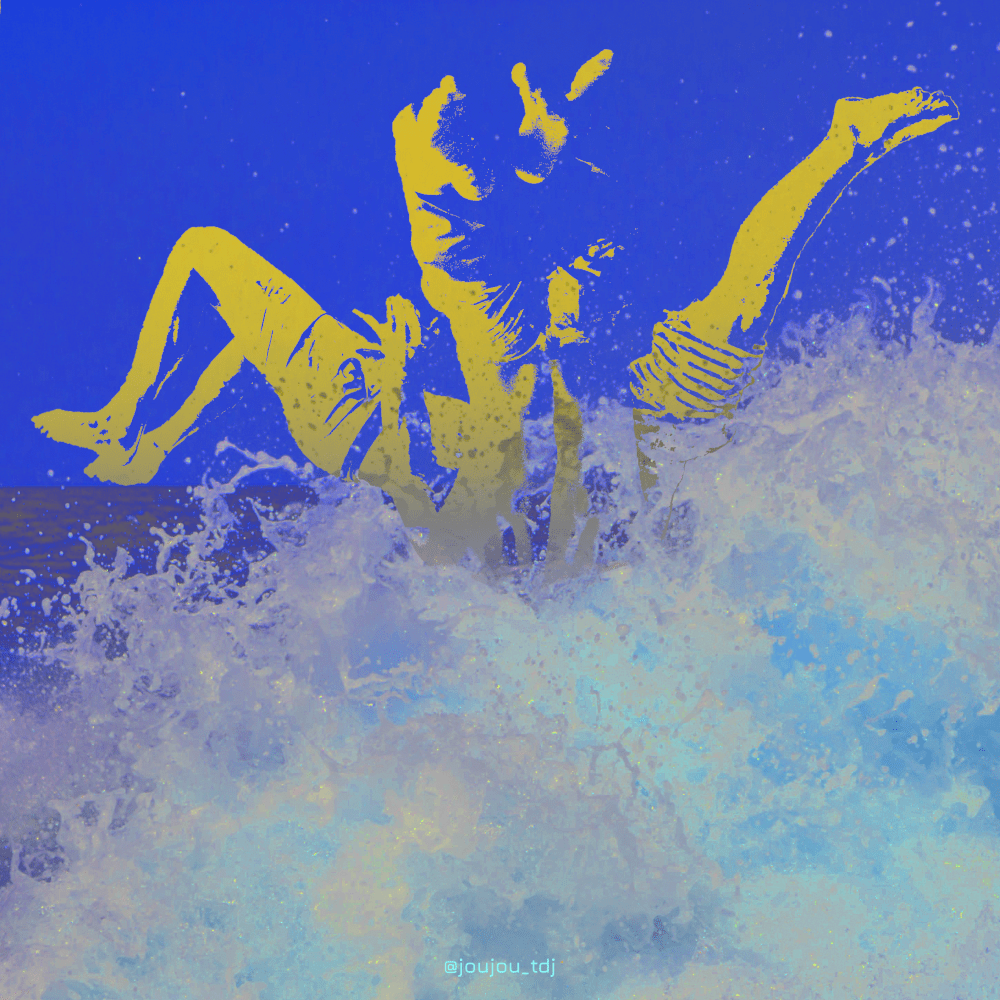

Contribution of @joujou_tdj

What I read about Oleg N. touched me.

When I read the article about him, I felt a great inner freedom with a strong desire to consume this freedom. I think that he is a man who did not allow himself to be subjugated. He was the target of violent oppression, but I think he was stronger than that.

The images I created do not go together well, but each one represents an aspect that I wanted to express, as parts of a complex reality.

Plonger (dive)

Aimer (love)

Résister (resist)

Partir (leave)

For Oleg.