Written by Âama – corrected version 1.2

Suicide is a process of self-destruction.

First it takes place internally, where the person disconnects with their-self, believing that their existence has no meaning or value. This is the longest and most difficult part of suicide, full of clinging, searching for hope and despair. And then the destruction takes place externally, the person also severs the connection between their body and the world. Everyone is interested in this part of the process, voices are only heard at this stage, the law imposes consequences not on internal destruction but on external destruction and the state-statistics only count these. This is what drives people and their tears, but it is not what the person who couldn’t survive needs. Where was the last city they managed to arrive, when was the last day they managed to endure, which was the last judgment they managed to stand, what was the last challenge they managed to struggle; those are only the concerns of those left behind. It is the long process of self-destruction that takes place before the final moment that concerns Alireza and that must be dealt with. Even though this article is being written at a time that is no longer meaningful for him, I want to draw the eye to a meaningful point and explain how for us, on the migration roads, in the camps, in everyday life, the self-destruction is happening gradually and how we are made to believe that our existence has no meaning or value.

For some of us, the story begins where we were born; Alireza was born in Afghanistan, in a place where, in a street interview in Switzerland, no one said yes to the question “Would you like to live in that country”. Those conditions, which no one associates with their self-worth and cannot even imagine living in, correspond to the daily life of someone playing, falling in love, dreaming, mourning, growing flowers, eating. How can we say that human life is valued the same in both geographies when what one part of the world experiences on an ordinary day is unimaginably horrifying in the eyes of the other part of the world? Especially when tons of money has been spent to separate one geography from the other with walls, guns, soldiers, mines and death traps. In the face of this reality, it is obvious that every person living in these horrible conditions will not be as inclined to believe that their life is meaningful and valuable as those in safe geographies.

Yes, for some of us, the process of internal destruction begins in the womb.

It would be a comfortable fallacy for the world of the privileged persons to think that this inequality is coincidental according to theories of divine birth conception, or arises from fateful circumstances due to geographical reasons. But no, the reality is that if someone’s piece of the pie of security, peace and value is smaller than the others, this is the result of multiple layers of power relationships and finally as of the greed of a few people. Since no resource in the world evaporates, it is not hard to guess that the peace and value that has been taken from us is also stored somewhere in abundance! This is why we are forced to make our way to the countries of prosperity to reclaim what is ours. From our horrible life, we leave behind all the memories, friendships, family and habits we have built in order to be able to breathe, the only things that made our life bearable, and we embark on an uncertainty that we know carries the risk of death. Being the person who feeds the neighborhood dog, being the big sister to her little brother, being the person who knows the place where she lives, being the neighbor who is asked to help… everything that gives meaning and value to our existence, we lose as a forced consequence of migration.

Those of us who are lucky enough to survive the migration route and reach prosperous countries hope that the world of worthlessness into which we were born and which has been riveted on our backs through migration, will come to an end and our existence will be worth something. They expect to be able to become a person endowed with rights, to have their material and moral existence deemed worthy of protection, and to finally receive their share of the security and peace pie.

They expect this not only on the basis of the fact that the states that have stolen their self-worth, which they must have been endowed with naturally owe them a life. They also expect it from states on the basis of the promises they make in international treaties and national law, on the basis of marketing themselves with human rights standards and making profits/investments out of it. But what we find in these countries in return for this perfectly justified expectation is a huge gap: the gap between the reality that in a fair order all people would be born with equal value and no one would have to migrate, and the reality that we couldn’t escape our worthlessness despite giving up everything we love and traveling thousands of death kilometers. Being a ‘stranger’ without ever once feeling that our existence is meaningful and valuable… The belief that there is something to be gained by continuing to live is hanging by a thread.

Even if the Swiss State Secretariat for Migration (SEM) meticulously fulfilled all its responsibilities, allocated sufficient resources to meet the needs of migrants, and created policies to repair all the damages and traumas we have suffered, we know that we cannot be equalized in this society with the weight of all our traumatizing experiences and memories. In this reality it’s not hard to imagine how much darker the picture is for migrants if the SEM does not do this job. Now let’s go even further and visualize SEM as one of the major obstacles thrown in our way when we are just trying to survive. Yes, this picture perfectly represents the position of SEM in our lives; we, as migrant survivors, live ‘despite’ the policies of this institution, not even with the support of this institution, not even with this institution’s ignoring us. Despite the historical and political responsibility of the Swiss State for our devalued lives, it deserves to be heard how devastating it is when it comes to fulfilling its debts/obligations. Even though they use different tools than the Taliban, Erdogan, Putin, Assad from whom we fled and try to show that there is no commonality between them, it deserves to be heard that they are exactly the same in terms of the effect they have on us.

We cannot live in the order established by any of them; they all tell us one thing: Your existence is not valuable or meaningful.

This is the word that has been whispered in my ear the most since the first day I had to get involved in the Swiss migration system. A word that no one said openly to me, no one shouted at me, no one hit me this sentence on the head; a word that is not written on the wall, that is not communicated by letter, that cannot not be found in the regulations, but that makes itself felt in all of this. Just as in my origin-country the police masterfully learned to inflict physical violence on our bodies without leaving a trace, in Switzerland the staff and policies of the immigration authorities have specialized in destroying our personalities and self-worth without any gaps or even, even with politeness. Not with the aggression of a dictator who openly declares that he does not recognize the constitution, but with the insidiousness of a heavy bureaucracy, always interpreting extremely ambiguous laws against us. I felt the same sense of worthlessness as an individual in front of both states, but while my country of origin was condemned by many institutions, Switzerland was portrayed the epitome of human rights and democracy. What we are experiencing in the Swiss migration system needs to be much more visible in order to unmask the cause of so many deaths and atrocities and in order to prevent further applause for the murderers who push us to the point of ending our lives.

I write this also with in mourning for the life of my friend who had to decide to continue her unplanned pregnancy due to the uncertainty and futurelessness caused by SEM and whose life withered away in front of my eyes.

The interview for the evaluation of her asylum application was terminated on the grounds that she could not talk about the traumas she has suffered in her country of origin because of crying. It had only been a few months since she had survived the persecution, she could not speak, that is how it was recorded. She was told that another interview would be arranged and that she would be contacted again, just wait. Two years have passed since that day and she has never been given another interview date, it has never been explained to her why it took so long, and she has not been shown anything meaningful she could do in the meantime. She can’t go to school, she can’t work, she can’t live in a house, she can’t travel, and she doesn’t know how long her life will continue like this. She has not been told to leave this country, but she has not been given a chance to live here. One day, the camp staff broke into the room where she was living and saw her lying on the floor, in the dirt, dust, clothes and food strewn on the floor, and thought she was dead! Then they realized that she was still alive but had lost her mental strength and they urgently transferred her from the camp to another place. Since her existence had no value and no meaning, the only thing they did was to treat this person who was losing her connection to life as a bomb of responsibility that was about to explode, and throw it out of their own hands and onto someone else. When we met recently, she told me that she had decided to continue her unplanned pregnancy in hopes of a better life and to stay in Switzerland. Before my eyes, in two years, Swiss migration policies had turned this young person’s life into a wreck, whereas I noticed her with her sparkling eyes at the first day she arrived in the camp where I was.

The places are they force us to live, the refugee camps are perhaps the most crystallized manifestation of official migration policy. They stack us on top of each other in the farthest parts of the city or in underground bunkers and only allow us to mix with life outside at limited times of the day. It is forbidden to engage in any activity in which we could earn money. The Swiss state locates us as if avoiding a plague epidemic, and it is impossible not to realize this. In their eyes, we do not belong to the human species that they value. What we are exposed to is similar to what animals are exposed to in terms of value given and treatment shown. Sometimes like the extras of the circus used to entertain, sometimes like individual helplessly imprisoned in zoos, and sometimes like those on animal farms, that are exploited from head to toe and then left to die. Being the subjects of our lives, our individuality, our abilities, our needs are not important there. We have only one name and one category: Migrants. Every morning we would go to the noticeboard of the camp to see if any new decisions had been made about our lives, we would look for our number (yes, everyone has a number, fortunately it is not nailed to our ears like it is to cattle!) and we would learn about the news about our asylum process.

While in our countries of origin we were labelled as rebels, victims of war, survivors, terrorists, damned, in the eyes of SEM we are not even those stigmas; we are no more than a number.

The meaninglessness and worthlessness of our existence are not only imposed through long-term general strategies; attacks on our dignity often manifested themselves in daily life too. The most obvious, even theatrical example of this in all the camps, are the ceremonies in which we are given our ‘pocket money’, which is determined as 3 CHF per day. Every Thursday between 08.00-09.00, everyone living in the camp is carefully lined up in a queue by the social workers,; every habitant, in turn,greets a high-ranking person from the SEM who is waiting with a cash register in hand. This SEM administrator asks hundreds of people with the same insensitivity, “Good morning, how are you?” and endows their weekly pocket money to refugees after each “I’m fine” answer. The person who receives the money thanks the SEM staffand leaves. This ceremony is the moment when the camp staff seem at their friendliest and most meticulous way. They often re-arrange the queues, warn the person who doesn’t realize it is their turn to go to the cashier, and direct the person who has taken their money towards the exit door. The line where we wait, where we enter the hall, where we take the money and leave is almost as precise as a chalk line on the floor. Of all the thousands of chaos and turmoil in the camp, this moment of giving the pocket money is the most flawless ceremony. it is reminiscent of theater in terms of staging, of the army in terms of power relations and greetings, and of the traditional father-child family relationship in terms of expectations of gratitude and respect. What makes it even more significant is that participation in this ceremony is obligatory. One day when I was sick and didn’t get in the pocket money queue, the camp staff came to my room and said that I had to go that queue.

It was clear that this whole ceremony was organized not to give us something, but to take something from us: Our dignity.

For the ridiculous price of 3 CHF per day, they want to take away our personality and replace it with grateful, ashamed, uniform, submissive, worthless objects. This is how they lay the foundation for the relationship betweenus and the Swiss state.

How can the state erode the mental health of migrants day after day without committing any physical violence, without committing any crime defined in the criminal code, with a shiny appearance that will score 10/10 in inspections? Switzerland seems to have written the “how-to” book on this topic. They have such a professional policy of depreciation that the victim faded day by day, suffers from psychosomatic illnesses, gives up on life, but can not understand who the perpetrator of this violence is. When you see that hundreds of people like you are forced to accept the same humiliating treatment, you lose your initial astonishment and adapt to the flow. Hundreds of other people have had to go through the same process as you to become ‘hundreds of people’. This is a result of the survival instinct, but also because of knowing that in this power relation your mandatory part is to submit. When you need toilet paper, it is shocking and humiliating for everyone to see that you have to go to the camp kiosk, return the empty toilet paper roll and exchange it for a new one. But since you have no other choice, you have to get used to waiting in line at the kiosk with the finished toilet paper roll. This situation takes away your sense of privacy, your self-worth, your awareness of your basic rights day by day. While you feel like nothing, you cannot understand that part of the reason for this nothingness is the empty toilet paper roll they make you carry. You feel humiliated only on the first day, the rest of the days you get used to living with your new ‘value’. That is the point of every measure of the Swiss immigration policies: to devalue you a little more and make you believe that you have no value.

These are not individual misfortunes, negligent managers, unregulated practices. On the contrary, these are thoroughly planned and undeniable general policies implemented in almost all camps, each carefully planned to produce exactly this result. There are also, of course, examples of crimes against migrants, but without addressing these “individual outbursts”, I would like to explain how even lawful practices can lead to the loss of self-esteem and the resulting self-destruction. What we experience can not be explained by technical reasons, economic inadequacies or security reasons. Because we know that if, for some reason, all of Switzerland’s politicians had to be kept in the same building for a while, that building and its policies would have been built from scratch in a way that would have been worthy of those politicians. The reason we are exposed to all this is because of the ‘value’ that the politicians have in tons and from which we are not given an ounce. So I will continue to talk about the routine/innocent practices of daily life in the camp and invite everyone to imagine what would happen if they were practiced on people with ‘value’.

For example, if we buy something like a shampoo, a pack of cigarettes or a bottle of fruit juice with the 3 CHF that they give us every day, we are expected to prove that we did not steal it by showing a ticket . Otherwise, non-invoiced goods are confiscated as evidence of a crime. This is not done in secret; on the contrary, this rule is written in big letters at the entrance of every camp. I will probably never forget how I felt the day I had to wait for an hour at the entrance for the camp manager to come and make a decision! about the shoes I bought for 5 CHF without invoice at the flea market. I couldn’t even name what I was experiencing, I only knew that it was something that might be explained by their own law but that was not compatible with my worth as a human being.

Bag and body searches are searches are carried out at the entrance. Goods without a receipt will be seized. Hazardous objects will be confiscated.

In the camps, your bodies don’t belong to you, they’re monsters, things to control. Every day, another hand touches them, searches them. If it is decided that your body is not healthy, you are obliged to undergo medical procedures. If your allergy to dust is considered to be covid, you won’t even be tested, you’ll be quarantined for two weeks. If, despite yourself, it is decided that your body is healthy, you will face constant obstacles to access the care you need. The fact that you are worried about the baby’s health in your belly or that you cannot eat because you are not given food in accordance with your ethical values are problems thIat exceed the health value you deserve in their eyes and will be ignored.

You will quickly understand that all the measures taken in the name of health are not aimed at preventing you from getting sick, but to prevent you from spreading diseases.

You will be expected to use cleaning materials when you want to enter many places where security, social workers and administrators enter without taking any measures. Those materials, which are allocated only to refugees, are also ‘carefully’ protected against theft. In the camps there is always a glove to separate the bodies of refugees from the bodies of non-refugees. But that glove is never changed, the same glove that the security just touch on to check someone’s shoes can soon be around your neck. The boundaries between what is seen as dirty and what is not are determined by the distinction between those who are associated with refugees and those who are not.You will be expected to use cleaning materials to enter many places where security, social workers and civil servants enter without taking any precautions. Materialsallocated only to refugees are ‘carefully’ protected against theft. In the camps there is always a glove to separate the bodies of refugees from the bodies of non-refugees. But that glove is never changed, the same glove that the guard just put on to check someone’s shoes will soon feelyour neck. The boundaries between what is seen as dirty and what is not are determined by the distinction between what isassociated with refugees and what is not.

At any moment, camp staff can suddenly raid your rooms, look under the beds, open your wardrobe , rummage through the dustbins, look for evidence of crime. Once, during a search, when I was sick and in bed, the social worker came up to me, touched my face with the same glove she had just used to search to the dustbin, wanted to check if I had a fever. She didn’t do this with the intention of harming me or with the awareness of her action; it happened automatically, even in good faith, which was much more humiliating. It was not even targeted to me as a person, I didn’t even have a personality to distinguish myself from others. She did it on the basis of the worthlessness automatically assigned to me by being a refugee. It never crossed her mind, with the utmost spontaneity, that there might be a difference between the hygiene needs of my face and the hygiene level of the dustbin. But of course she had the reflex to protect her face with that glove when she needed to touch myface. What everyone knows deep down inside, but is forbidden to talk about, comes to the surface through such runconscious behaviors. We are worthless beings not only for the management of the SEM in Bern, but also for the lowest paid employees of the scale.

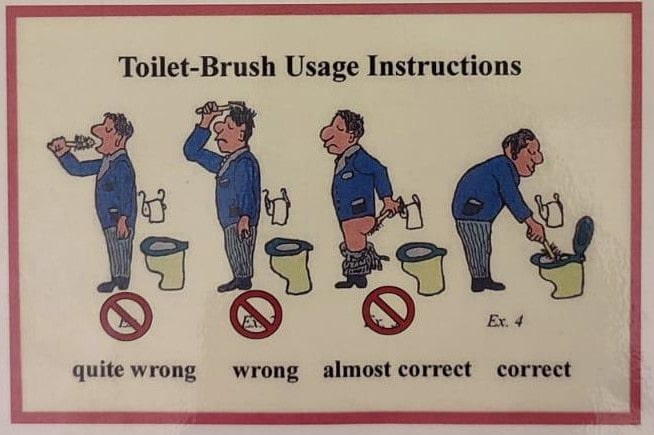

The posterswe encounter and what they are trying to teach us deserve to be examined in depth. All of them have been cleverly designed to easily block any criticism by the shield of their false benevolence. Herein lies the gravity of what we are already experiencing: They erode our self-worth day by day with their professional behaviors spread over time, but they never acknowledge what they are actually doing. In this way, the violence we suffer is not acknowledged, nor do we receive restorative apologies; it isalmost impossible for us to see that the feeling of worthlessness is not inherent to us, but is injected into us by the state. Toilet warning signs, which will not be encountered in any university, in any office, in any municipality, are hung on the toilets of SEM centers, and when you ask the reason for this, more or less every staff member justifies themselves in a similar way by gently insulting refugees. In different cantons, in different camps, it’s surprising how every official gives the same answers, as if they had taken the same class. In fact, this is exactly the case, all of them have learned their lessons from state policies, and they are all working together to put into practice the state mind. Funny, threatening, didactic… warnings are issued in different themes, but each time the asymmetrical power relationship between the author of the warning and the addressee of the warning manifests itself. For this reason, it is important to be seen what feelings the authority wants to evoke in us with the tool it uses as well as what it is trying to ‘teach’ us. For example, the posterabout not entering to camp with muddy shoes is made witha photo of the muddy shoes of a child living in that camp, printed and hung at the entrance. This is a very accurate picture of how the official migration policy relates to us. What that child feels every time he walks through the door is what SEM wants us to feel every time we are in this country. Theaim is not a clean environment, but to build this desired order on our shame.

The Swiss migration system does not give anything unless it is certain that it will get more in return. And the distribution of the insufficient budget it allocates is not based onneeds, but on whether it is a profitable investment in the future. For example, the system surrounds to isolate small children from their family, because these children are resources, projects that should not be missed. The state has the tools and the right to completely integrate them into its own system, and also it’s very profitable to create permanent gratitude by convincing them that the state offers them great opportunities that they do not deserve. However, in the case of migrants who are considered to be unlikely to participate in the labour force and the propaganda showcase of the country, such as disabled, elderly or anti-authoritarian migrants, access to resources for basic survival is always at risk as the state may not be able to profit from it.

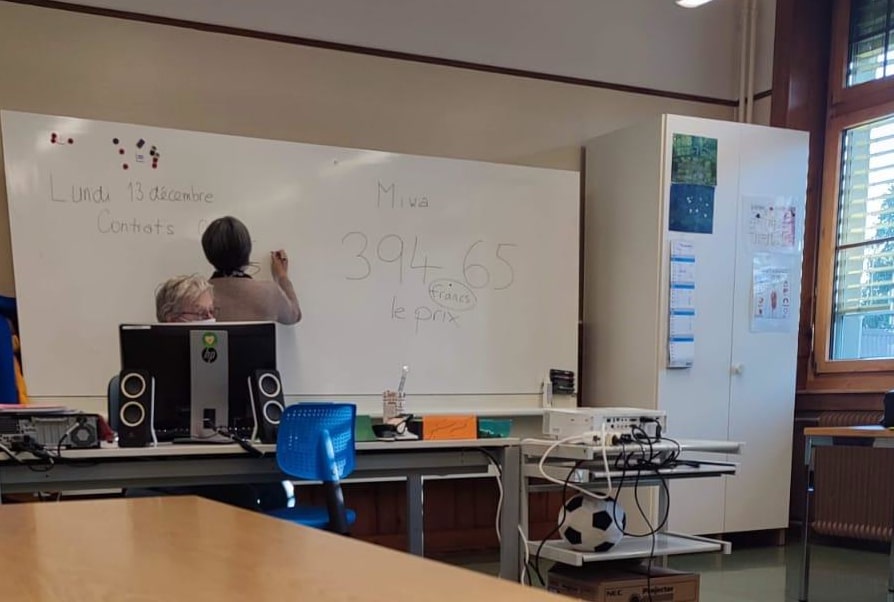

In any case, theseinsufficient and so-called refugee-allocated resources are transferred from one institution to another without the refugees being able to touch them or freely decide how to manage them. In fact, while the money circulates among state institutions without ever leaving, the state always demands a return on an investment it has never paid. The language courses we are compulsorily sent to are a clear example of this. When it’s examined who runs the courses and how they relate to refugees, it will be seen that it is the state that benefits from these courses, not the refugees. These courses are provided by public companies working for SEM; for each student, the state takes money from one pocket and puts it in another, invoicing it to us. In the meantime, the learning we are given is not at all conducive to developing any language skills. These trainings allow , tounderstand what is officially communicatedto us, to thank the police when they ask for our identity card, to immediately carry out the instructions given to us and, one day, to go to the counter and pay our taxes. Despite all this mise en scene, we are expected to be grateful to the SEM for allocating resources to us. With this purpose, an administrator from the SEM comes to visit our class and spends an hour telling us what lucky victims we are for attending these courses! When, in front of dozens of people, she writes the amount of money paid for these courses, it does not even cross her mind that we have enough ‘value’ to understand the impudence of this. However, she was wrong, the worthless ones would immortalize this moment by photographing it and call her to account for it:

-Yes, children, do you pay for these courses?

– No, madam.

– And do you know how much these courses cost per month?

– No, madam.

-Then look carefully, I’m writing on the board.

-…………….

– Who do you think gives this money? I’ll take guesses.

– State, SEM, CARITAS, ORS, Canton….

– No, guys, you don’t know, we as citizens pay this money. You come here with our taxes.

-…………….

– Do you know what a tax is? -Oh you know this. All right, so don’t forget that.

Even the most well-intentioned and thoughtful actions taken by the state ‘in favour of refugees’ are based on the official assumption that we are worthless people, so at the end of the day they all turn into actions ‘against refugees’. But what we have experienced in our life in Switzerland is much more than this binding causal link created by reason of state.

IThe fact that they take us out on the streets on certain days of the year, escorted by the police,to teach us how to walk on the road and how to cross the street,is not possible to interpret as goodwill but clumsily translated into action . Because it is quite obvious that this march of shame, organised in the name of education, in which participation is compulsory, is far removed from the daily life of anyone living in this country. This is evident from the way the people living around watch us from their balconies as if we are part of a circus, while we are trying to walk from one side to the other and bumping into each other under stress. We walk with the awareness that no one of those who organizes, manages, supervises or watches this “exercise” would accept to see themselves in this position, within a few meters of them, at a distance where the difference in value between us can hit us in the face. We are forced to stomach this spectacle of devaluation because we fear that the endless chain of cause and effect of not doing something that is said to be obligatory could lead to us being sent back to the countries where we were traumatized. Every migrant, without exception, has to build their life more or less in the shadow of this concern. As long as this concern exists, it doesn’t matter whether it is realistic, exaggerated, ignorant, possible, unlawful, cowardly, irrational… etc. For someone who had to leave their place of residence, knowing that this eventuality is somehow possible creates an “self-respect gap” impossible to close between them and someone who does not live with this possibility, which affects their every choice. As long as the sword of ‘deportation’ hangs over us, we will never be able to feel the ‘value’ that would protect us from self-destruction. As a first step in restoring our usurped value, the system of ‘deportation’, which turns us from being someone into something, must be abolished, immediately.

Huge hands holding us by the head as if we were pieces of a game tthat carry us from one place to another… a state that drawsa line around a region and to say we cannot live here although we are naturally part of this world, which turns us into an object like a cargo package with a label on us that says sender: Switzerland receiver: Greece… An institution directorhas the power to cut,forever, our ties with the country where we have built a new life. I am talking about something unbearable and beyond them: We are being sent back to countries where we have been traumatised, where these traumas are ignored, where no one has any intention of repairing them.

We are officially being sent back to the cruelty we have suffered and managed to escape from. Greece, Croatia, Slovenia… unfortunately for many refugees these are not just names of countries. In our memories, these names represent places where we are expected to drown in their rivers and freeze in their forests; where we are beaten in the registered areas, stripped and thrown in the middle of nowhere in the unregistered areas, where all these are not punished as a result of their state policy. We don’t even have the privilege of being able to talk about these countries without getting goosebumps. Many of my friends say that even if one day they were given Swiss citizenship, security guarantees and economic opportunities, they would not be able to Greece even for a holiday. In the face of all this information, I know how devastating it was to tell “Now, you have to go back to Greece” to 18-year-old Alireza, who managed to escape the war in Afghanistan as a child, who survived the sexual violence he was subjected to in a camp in Greece, who finally reached Switzerland and managed to build a new life here. They know this too. They, the SEM officials who made this deportation decision against Alireza.

Alireza ended his life in Geneva on 30 November 2022, just after the Swiss Federal Administrative Court (TAF) notified him of this decision. The TAF and the SEM made this decision despite knowing from medical reports that the deportation decision could cost Alireza his life. Following his death, SEM Press Secretary Anne Césard perfectly represented Switzerland’s immigration policy and her criminal organisation that killed Alireza in her shameless statement:

“The risk of suicide is not an obstacle to the deportation decision, otherwise they could not send anyone back, the procedures carried out were in accordance with the law.” Meanwhile there were news reports, public debates and protests; the decision was condemned, someone to be blamed was seeked; some were angry, some were sad… But while all this was happening, Alireza was not there, when he was finally recognised as a person and being somewhat valued at last. At a senseless time for him, suddenly many politicians began to say that they felt sorry for Alireza. Nevertheless, his adventure of running after the value that was stolen from the day he was born to the day he passed awaywas not sad enough for anyone. This is exactly why, despite the hundreds of terrible politicians, the immigration policies and xenophobia that have devalued Alireza since his arrival in Switzerland, we must oppose with all our might the fact that everyone’s eyes are fixed on the last moment of suicide, when the responsibility bomb exploded. It was a collective and long-termeffort that oppressed, frustrated, discouraged and despaired Alireza day by day. How he lived should have been as newsworthy as how he died.

We are migrants who have managed to survive for today despite the systematic destruction of our self-esteem by Swiss immigration policies, but who are not too far from the abyss Alireza was pushed into. We are people who are forced to dance on the tiny line between life and destruction because of where we were born or where we migrated to. When we do not die, we cannot live as we deserve. Despite the dynamite that has been placed installed all over our daily lives, we are still standing with our own resources, tools, friends and solidarity. For this precise reason, while suicide is a process of self-destruction, surviving turns into a riot of resistance and solidarity. In this riot, in which we involuntarily find ourselves, our biggest defense tool is to remember that “we have our value simply because we exist, no authority can give it to us or take it away from us.” Believing and internalizing this is not easy in the conditions we are pushed into, so as a step towards this, I invite us to speak out loud and publish through this platform about what we are facing and what we deserve before we feel helpless and worthless. Let’s strengthen our confidence that our existence is valuable and make attentions draw to our lives lives in order to avoid furtherdeaths.

Tell your story, shout your worth to those who try to devalue you.

Let us be seen, before we die. beforewedie@riseup.net